One Language, Two Worlds: Learning Chinese 35 Years Ago and Today

by Marcia Yudkin

While making plans to follow China’s old Silk Road next year on a driving trip, I dug out the textbooks I’d used to study Chinese when I lived and worked in Beijing in 1983-84. Through an improbable combination of circumstances, I’d landed a September-to-September job as a writer and editor for the English-language section of the Foreign Languages Press. For me, the job in China was like a chance to go to the dark side of the moon.

In those days, China had recently re-opened to the West, and few Americans had visited. As soon as I knew I was going, I bought the Foreign Service Institute’s Chinese course on audio cassettes and started in on greetings, how to order a taxi, get a haircut and so on. I was determined to make the most of my year-long adventure and not live in an expat bubble.

By the time I arrived in Beijing, I could handle a basic conversation in Chinese. Everyone I worked with spoke very good English, but at my request, they set me up with a tutor who came to my hotel apartment every Tuesday and Thursday evening. During the noon break at the office, when most of my Chinese colleagues napped and the other foreign experts got bussed back to the Friendship Hotel for a Western lunch, I worked my way slowly through the orange-covered volumes of the Elementary Chinese Readers.

Along with a newly made friend from the French section of the Foreign Languages Press, I took train journeys to places like Datong, Chengdu, Xian and Tai Shan on weekends and holidays. Outside of Beijing, children would jump up and down shouting “Waiguo ren! Waiguo ren!” (“Foreigner!”) when they saw us. On the train in “hard seat,” adults who didn’t just stare at us as if we were blue-eyed ghosts chatted with us about family, destinations, origins and our lifestyle back home.

After leaving China, I retained a lot of my conversational ability but lost my ability to read. So to make the most of the upcoming Xian-to-Kashgar road trip, I began going through the orange-covered Chinese readers again. Many articles felt familiar as I re-studied them, like the story about the old man who wanted to move the mountain and the chapter about Lenin refusing to eat anything except black bread, just like his struggling comrades.

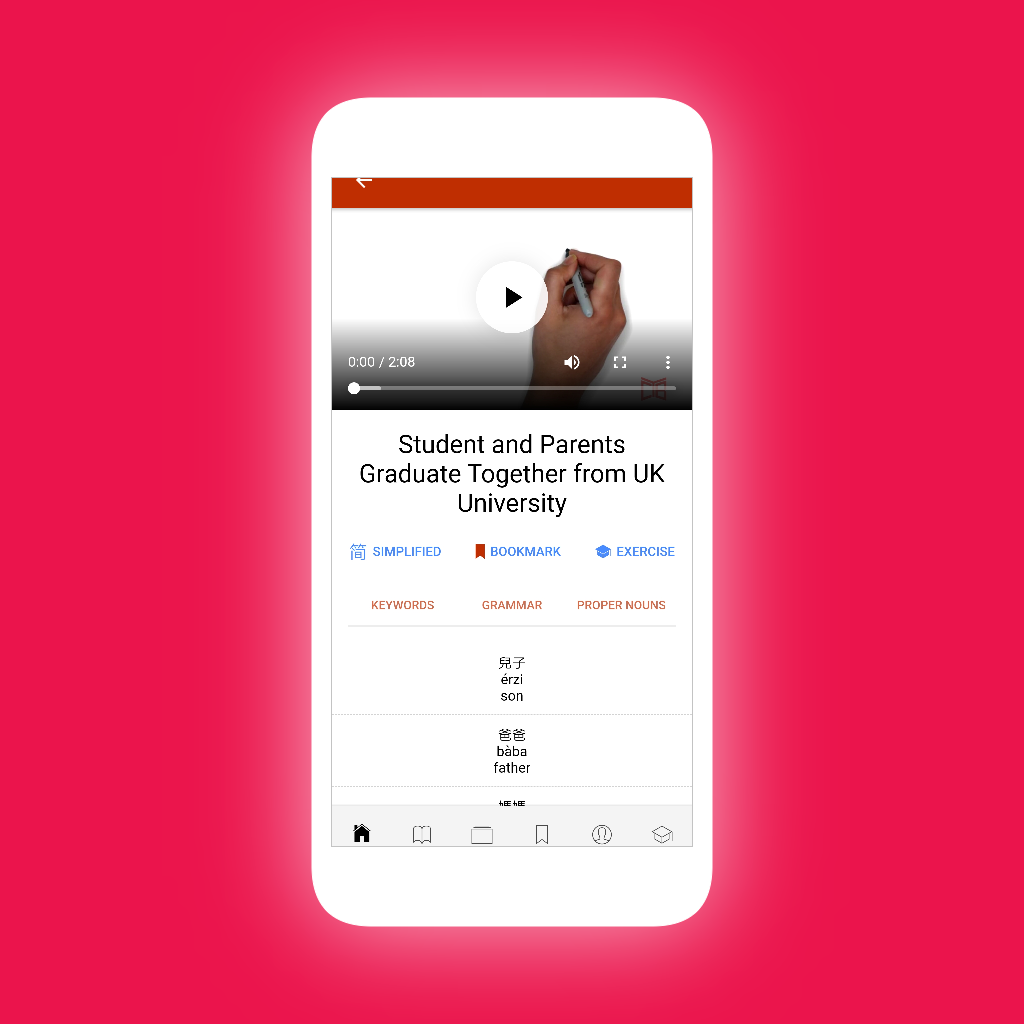

However, not until I discovered The Chairman’s Bao, with its jazzy full-color photos and thoroughly up-to-date pieces about incidents like schoolkids having their mobile phones confiscated by teachers did the contrast between the China of my 1980s textbooks and its everyday life today fully hit me.

In the Elementary Chinese Readers, typical vocabulary included “socialism,” “after Liberation,” “brave soldier” and “feudal.” Where they talked about economic development, they meant people in the countryside still farming with donkeys and hand tools but having enough to eat.

In China of the early 1980s, such Maoist content did not seem badly out of date. A campaign against “spiritual pollution” revved up while I was there, and all my Chinese co-workers, whether Communist Party members or not, had to attend political study sessions. In the translated English material that I edited, words like “cadre” and “comrade” were common, although we were encouraged to use “farmer” now instead of “peasant.”

An atmosphere of scarcity still reigned while I was there, as well. At the office, we had to present ration tickets for rice or noodles along with cash when we placed our lunch order at the cafeteria window. Transportation of food from the warmer South was rare, so that during the winter, the only vegetable regularly available in Beijing was cabbage, with cauliflower or tomatoes an occasional treat.

Aside from a few so-called “free markets,” where raggedy country people sold sweet potatoes, live chickens or ducks in the streets, residents bought food, clothing and other needs at state-run stores. Entrepreneurship was just re-emerging, mainly among those who were social outcasts in one way or another, and my unit assigned me to write a book about this phenomenon, which they published as Making Good: Private Business in Socialist China. At Spring Festival time, my boss went around greeting everyone with “Gongxi Facai” – a traditional wish for a prosperous new year that he told me had not been used on the mainland in a generation.

No one had running hot water at home. They showered at the office bathhouse, with two days a week set aside for women, and two for men. My Chinese co-workers had rarely ever ridden in a car, and a Chinese guy my age told me that he could remember a book of paper matches being a technological novelty when he was young.

To my eyes, the physical environment at that time was disturbingly drab. Women and men alike wore dark blue Mao jackets most of the year. In the spring, only a few parks had grass and flowers, because authorities had long believed that greenery spread bugs. Dirt blew everywhere when it was windy. Many of the gray Soviet-style concrete buildings in the city had long cracks on their inside walls from the 1976 Tangshan earthquake, which had killed more than half a million people a bit to the east.

Even a quick look at the photos and headlines on The Chairman’s Bao makes clear the monumental change China has experienced since those years. Streets, homes, schools and offices are now bursting with color. Economic prosperity means sleek high-rises, smartphones in almost everyone’s pocket (or hand), year-round abundance of food and the same kinds of leisure pursuits as in Europe or America.

Vocabulary lists on The Chairman’s Bao include phrases like “mobile payment,” “consumer goods,” “fashion show” and “market cap” that either did not exist or would have been esoteric in China 35 years ago. Stories about young and old people striking it rich with a clever idea and hard work abound. Occasional pieces about Buddhist monks, Taoist priests or Bible printings show that even religion has a place in today’s China.

In Volume 4 of the Elementary Chinese Readers, I left off at a lesson about heroics at a people’s commune. I think I’ll return those orange-covered textbooks to my basement and study up instead on “Chinese Robot Passes Medical Exam,” “Old Couple Become Internet Celebrities Through Online Streaming,” and “Alibaba Steps Up Promotion for Cashless Society.” And when I’m next in China, I’ll have the words to talk about apps, ambitions, amusements and zany news like self-heating instant noodles.

Marcia Yudkin (www.yudkin.com) is the author of 17 books, including 6 Steps to Free Publicity. Currently she helps introverts and business owners create authentic, effective marketing strategies.